New vulnerability found in HIV virus gives potential for new vaccine

24 April 2014

A new vulnerable site on the HIV virus that doesn't mutate or vary between strains has been identified by a team led by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) working with the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI). The new site can be attacked by human antibodies in a way that neutralizes the infectivity of a wide variety of HIV strains.

The discovery is part of a large, IAVI- and NIH-sponsored effort to develop an effective vaccine against HIV. Such a vaccine would work by eliciting a strong and long-lasting immune response against vulnerable conserved sites on the virus — sites that don’t vary much from strain to strain, and that, when grabbed by an antibody, leave the virus unable to infect cells.

HIV generally conceals these vulnerable conserved sites under a dense layer of difficult-to-grasp sugars and fast-mutating parts of the virus surface. Much of the human body's antibody response to infection is directed against the fast-mutating parts and thus is only transiently effective.

The findings were reported in two papers appearing in the May issue of the journal Immunity.

“HIV has very few known sites of vulnerability, but in this work we’ve described a new one, and we expect it will be useful in developing a vaccine,” said Dennis R. Burton, professor in TSRI’s Department of Immunology and Microbial Science and scientific director of the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center (NAC) and of the National Institutes of Health’s Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology and Immunogen Discovery (CHAVI-ID) on TSRI’s La Jolla campus.

“It’s very exciting that we’re still finding new vulnerable sites on this virus,” said Ian A. Wilson, Hansen Professor of Structural Biology, chair of the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology and member of the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at TSRI and member of the NAC and CHAVI-ID.

Prior to the new findings, scientists had been able to identify only a few different sets of “broadly neutralizing” antibodies, capable of reaching four conserved vulnerable sites on the virus. All these sites are on HIV’s only exposed surface antigen, the flower-like envelope (Env) protein (gp140) that sprouts from the viral membrane and is designed to grab and penetrate host cells.

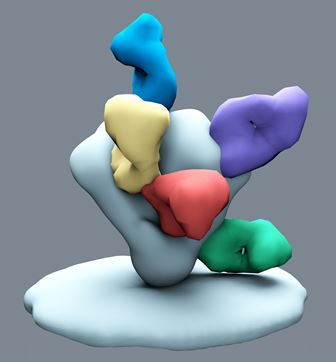

An electron microscopic reconstruction of the

HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer (pale blue) with antibodies

representing each site of vulnerability in different colours,

including the newly discovered PGT151 shown in red. (Image by

Christina Corbaci, courtesy of The Scripps Research Institute.)

The identification of the new vulnerable site on the virus began with tests of blood samples from IAVI Protocol G, in which IAVI and its NAC partnered with clinical research centres in Africa, India, Thailand, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States to collect blood samples from more than 1,800 healthy, HIV-positive volunteers to look for rare, broadly neutralizing antibodies.

The serum from a small set of the samples indeed turned out to block the infectivity, in test cells, of a wide range of HIV isolates, suggesting the presence of broadly neutralizing antibodies. In 2009, scientists from IAVI, TSRI and Theraclone Sciences succeeded in isolating and characterizing the first new broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV seen in a decade.

Emilia Falkowska, a research associate in the Burton laboratory who was a key author of the first paper, and colleagues soon found a set of eight closely related antibodies that accounted for most of one of the sample’s HIV neutralizing activity. The scientists determined that the two broadest neutralizers among these antibodies, PGT151 and PGT152, could block the infectivity of about two-thirds of a large panel of HIV strains found in patients worldwide.

Curiously, despite their broad neutralizing ability, these antibodies did not bind to any previously described vulnerable sites, or epitopes, on Env — and indeed failed to bind tightly anywhere on purified copies of gp120 or gp41, the two protein subunits of Env. Most previously described broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies bind to one or the other Env subunit. The researchers eventually determined, however, that PGT151 and PGT152 attach not just to gp120 or gp41 but to bits of both.

In fact, gp120 and gp41 assemble into an Env structure not as one gp120-gp41 combination but as three intertwined ones — a trimer, in biologists’ parlance. PGT151 and 152 (which are nearly identical) turned out to have a binding site that occurs only on this mature and properly assembled Env trimer structure.

“These are the first HIV neutralizing antibodies we’ve found that unequivocally distinguish mature Env trimer from all other forms of Env,” said Falkowska. “That’s important because this is the form of Env that the virus uses to infect cells.”