Taking aspirin long-term halves risk of hereditary cancers

28 October 2011

A decade-long study in 16 countries has found that taking 600mg aspirin every day for over five years halves the risk of getting hereditary cancers.

Hereditary cancers are those that develop as a result of a gene fault inherited from a parent. Bowel and womb cancers are the most common forms of hereditary cancers.

The study, which is published in The Lancet [1], involved scientists and clinicians from 43 centres in 16 countries. The trial was overseen by Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. It followed nearly 1,000 patients with Lynch syndrome, in some cases for over 10 years. Lynch syndrome is an inherited genetic disorder that causes cancer by affecting genes responsible for detecting and repairing damage in the DNA. Around 50% of those with Lynch syndrome develop cancer, mainly in the bowel and womb.

Evidence of the benefits of aspirin has been accumulating for

over 20 years but these are the first results from a randomised

controlled trial assessing the effect of aspirin on cancer.

Evidence of the benefits of aspirin has been accumulating for

over 20 years but these are the first results from a randomised

controlled trial assessing the effect of aspirin on cancer.

The study

Between 1999 and 2005 a total 861 people began either taking two aspirins (600 mg) every day for two years or a placebo. At the end of the treatment stage in 2007 there was no difference between those who had taken aspirin and those who had not.

However, the study team anticipated a longer-term effect and designed the study for continued follow-up. By 2010 there had been 19 new colorectal cancers among those who had received aspirin and 34 among those on placebo. The incidence of cancer among the group who had taken aspirin had halved —and the effect began to be seen five years after patients starting taking the aspirin.

A further analysis focused on the patients who took aspirin for at least two years and here the effects of aspirin were even more pronounced: a 63% reduced incidence of colorectal cancer was observed with 23 bowel cancers in the placebo group but only 10 in the aspirin group.

Looking at all cancers related to Lynch syndrome, including cancer of the endometrium or womb, almost 30% of the patients taking the placebo had developed a cancer compared to around 15% of those taking the aspirin.

Those who had taken aspirin still developed the same number of polyps, which are thought to be precursors of cancer, as those who did not take aspirin but they did not go on to develop cancer. It suggests that aspirin could possibly be causing these cells to destruct before they turn cancerous.

Over 1,000 people were diagnosed with bowel cancer in Northern Ireland last year; 400 of these died from the disease. Ten per cent of bowel cancer cases are hereditary and by taking aspirin regularly the number of those dying from the hereditary form of the disease could be halved.

Underlying mechanism

The researchers believe the study shows that aspirin is affecting

an underlying mechanism which predisposes someone to cancer and that

further study is needed in this area. Since the benefits are

occurring before the very early stages of developing a tumour —

known as the adenoma carcinoma sequence — the effect must be

changing the cells that are predisposed to become cancerous in

later years.

The researchers believe the study shows that aspirin is affecting

an underlying mechanism which predisposes someone to cancer and that

further study is needed in this area. Since the benefits are

occurring before the very early stages of developing a tumour —

known as the adenoma carcinoma sequence — the effect must be

changing the cells that are predisposed to become cancerous in

later years.

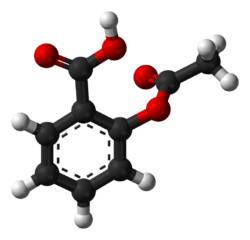

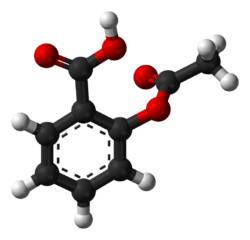

One possibility is that a little recognised effect of aspirin is to enhance programmed cell death. This is most obvious in plants, which release salicylic acid when under stress such as from drought, or under attack from fungus or insects. It helps diseased plants contain the spread of infection. Aspirin was first isolated from willow bark in 1829, but the medicinal use of willow bark to treat headaches, pain and fevers was recorded by Hippocrates (460-377 BC).

Implications

Professor Patrick Morrison from Queen’s University in Belfast, who led the Northern Ireland part of the study, said: “The results of this study, which has been ongoing for over a decade, proves that the regular intake of aspirin over a prolonged period halves the risk of developing hereditary cancers. The effects of aspirin in the first five years of the study were not clear but in those who took aspirin for between five and ten years the results were very clear.”

“This is a huge breakthrough in terms of cancer prevention. For those who have a history of hereditary cancers in their family, like bowel and womb cancers, this will be welcome news.

"Not only does it show we can reduce cancer rates and ultimately deaths, it opens up other avenues for further cancer prevention research. We aim now to go forward with another trial to assess the most effective dosage of aspirin for hereditary cancer prevention and to look at the use of aspirin in the general population as a way of reducing the risk of bowel cancer.

“For anyone considering taking aspirin I would recommend discussing this with your GP first as aspirin is known to bring with it a risk of stomach complaints, including ulcers.”

The international team are now preparing a large-scale follow-up trial and want to recruit 3,000 people across the world to test the effect of different doses of aspirin. To take part in the next trial people can sign up at www.capp3.org

Further information

1. Burn J et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, Early Online Publication, 28 October 2011. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61049-0.

A summary and full list of authors and institutions involved is

available at:

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/

PIIS0140-6736%2811%2961049-0/fulltext

2. Over the course of the clinical trial, funding came from Cancer Research UK, UK Medical Research Council, European Union, Bayer Corporation, National Starch and Chemical Company, The Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Bayer Pharma. Further international funding was provided by: Newcastle Hospital Trustees, Cancer Council of Victoria Australia, THRIPP South Africa, The Finnish Cancer Foundation, and SIAK Switzerland.