Genome sequencing traces cholera pandemic back 40 years to Bay of Bengal

24 August 2011

Advanced genome sequencing has shown that the latest cholera pandemic can be traced back to an ancestor that first appeared 40 years ago in the Bay of Bengal. Researchers have also highlighted the impact of the acquisition of resistance to antibiotics on shaping outbreaks and show resistance was first acquired around 1982. From this ancestor, cholera has spread repeatedly to different parts of the world in multiple waves, the current outbreak being the seventh.

These findings offer much better understanding of the mechanisms behind the spread of cholera — a diarrhoeal infection which is usually linked to unhygienic conditions and poor sanitation systems often found in disaster areas, such as the Haitian earthquake in October 2010. It is estimated that cholera affects 3 million to 5 million people each year, with 100,000–120,000 deaths.

The research team, led by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, tracked the spread of the organism by analysing the genomes of the causative bacterium Vibrio cholerae taken from 154 patients across the world over the last 40 years. Using the ability to track single DNA changes in the genome of this strain, they were able to map the transmission routes of the bacteria, aiding future health planning and enabling ‘backtracking’ of the disease to its origin.

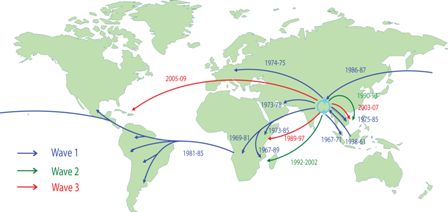

Transmission events inferred for the seventh

cholera pandemic phylogenetic tree drawn on a global map

They discovered that the current strain of the bacterium — known as the El Tor strain — first became resistant to antibiotics in 1982 by acquiring the genetic region SXT, which entered the bacterium’s genome at that time, triggering renewed global transmission from the original source.

“Through comparing the genomes of 154 cases of cholera, we have made important discoveries as to how the pandemic has developed” says Dr Julian Parkhill, a senior group leader at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and a senior author of the study. “Our research shows the importance of global transmission events in the spread of cholera. This goes against previous beliefs that cholera always arises from local strains, and provides useful information in understanding cholera outbreaks.”

The study crucially identified the origins of the pandemic strain to its roots 40 years ago in the Bay of Bengal. From this base, it has since infected people around the world, including Africa, South Asia and South America.

“Looking at the past 40 years of transmissions from continent to continent, we found that the Bay of Bengal acts as a reservoir for cholera, where it can thrive and spread,” explains Nicholas Thomson from the Sanger Institute and one of the first authors of the study. “By tracking how the disease is spread, our maps of transmission could influence future decisions on how to tackle this disease.”

The analysis shows that there was not a simple single spread of a strain of V. cholerae out from the Bay of Bengal. The evidence suggests that there have been at least three independent overlapping waves of intercontinental spread with a common ancestor in the 1950s, representing the original El Tor strain. These movements are strongly correlated with human activity, suggesting that the strain has been carried by human travel.

“These findings are opening up new pathways for researchers studying all fields of bacterial infection: from investigating how genetic changes enable strains to build up resistance to antibiotics, to being able to track a disease’s transmission and trace it back to its roots,” says Ankur Mutreja, first author from the Sanger Institute. “These first initial discoveries could be the key to unlocking many other bacterial pandemics.”

“This is among the first study that merges evolutionary information with emergence of contemporary new variants of Vibrio cholerae and then uses the phylogenetic signatures to track the intercontinental spread of cholera,” explains Professor G Balakrish Nair, Director of the National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases in Kolkata, India. “These findings in due course will lead us to understand why cholera pandemics begin in Asia and then spread as a wave across the world.”

Further information

1. Mutreja A, Kim DW, Thomson N et al. Evidence for several waves of global transmission in the seventh cholera pandemic. Nature, published online 24 August 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10392

2. Institutions participating in the research:

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK

- International Vaccine Institute, Kwanak, Seoul, Korea

- Department of Pharmacy, Hanyang University, Kyeonggi-do, Korea

- Seoul National University, Gwanak-gu, Seoul, Korea

- Centre for Microbiology Research, KEMRI at Kenyatta Hospital Compound, Kenya

- Department of Microbiology and Immunology and University of Gothenburg Vaccine Research Institute, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden

- National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases, Beliaghata, Kolkata, India

- University of Cambridge, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Cambridge, UK.