Microelectronic sensors could replace multi-welled microplate in research labs

23 Sept 2010

The multi-welled microplate, long a standard tool in biomedical research and diagnostic laboratories, could be replaced by new electronic biosensing technology on a chip developed by a team of microelectronics engineers and biomedical scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Microplates, which are arrays of small test tubes, have been used for decades to simultaneously test multiple samples for their responses to chemicals, living organisms or antibodies. Fluorescence or colour changes in labels associated with compounds on the plates can signal the presence of particular proteins or gene sequences.

The microplates themselves have been progressively shrinking over the years, but the marriage of electronics with biotechnology could see them replaced altogether — along with the associated laboratory equipment used to analyse their contents automatically and capture the resulting data.

The researchers hope to replace these microplates with modern microelectronics technology, including disposable arrays containing thousands of electronic sensors connected to powerful signal processing circuitry. If they’re successful, this new electronic biosensing platform could help realize the dream of personalized medicine by making possible real-time disease diagnosis — potentially in a physician’s office — and by helping select individualized therapeutic approaches.

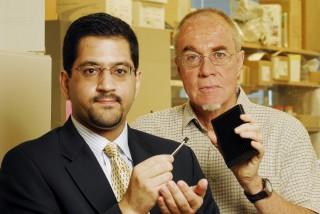

Associate professor Muhannad Bakir (left) holds

a prototype

electronic microplate, while Professor John McDonald

holds

an example of the conventional microplate it will replace.

“This technology could help facilitate a new era of personalized medicine,” said John McDonald, chief research scientist at the Ovarian Cancer Institute in Atlanta and a professor in the Georgia Tech School of Biology. “A device like this could quickly detect in individuals the gene mutations that are indicative of cancer and then determine what would be the optimal treatment. There are a lot of potential applications for this that cannot be done with current analytical and diagnostic technology.”

Fundamental to the new biosensing system is the ability to electronically detect markers that differentiate between healthy and diseased cells. These markers could be differences in proteins, mutations in DNA or even specific levels of ions that exist at different amounts in cancer cells. Researchers are finding more and more differences like these that could be exploited to create fast and inexpensive electronic detection techniques that don’t rely on conventional labels.

“We have put together several novel pieces of nanoelectronics technology to create a method for doing things in a very different way than what we have been doing,” said Muhannad Bakir, an associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

“What we are creating is a new general-purpose sensing platform that takes advantage of the best of nanoelectronics and three-dimensional electronic system integration to modernize and add new applications to the old microplate application. This is a marriage of electronics and molecular biology.”

The three-dimensional sensor arrays are fabricated using conventional low-cost, top-down microelectronics technology. Though existing sample preparation and loading systems may have to be modified, the new biosensor arrays should be compatible with existing work flows in research and diagnostic labs.

“We want to make these devices simple to manufacture by taking advantage of all the advances made in microelectronics, while at the same time not significantly changing usability for the clinician or researcher,” said Ramasamy Ravindran, a graduate research assistant in Georgia Tech’s Nanotechnology Research Center and the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

A key advantage of the platform is that sensing will be done using low-cost, disposable components, while information processing will be done by reusable conventional integrated circuits connected temporarily to the array. Ultra-high density spring-like mechanically compliant connectors and advanced “through-silicon vias” will make the electrical connections while allowing technicians to replace the biosensor arrays without damaging the underlying circuitry.

Separating the sensing and processing portions allows fabrication to be optimized for each type of device, notes Hyung Suk Yang, a graduate research assistant also working in the Nanotechnology Research Center. Without the separation, the types of materials and processes that can be used to fabricate the sensors are severely limited.

The sensitivity of the tiny electronic sensors can often be greater than current systems, potentially allowing diseases to be detected earlier. Because the sample wells will be substantially smaller than those of current microplates — allowing a smaller form factor — they could permit more testing to be done with a given sample volume.

The technology could also facilitate use of ligand-based sensing that recognizes specific genetic sequences in DNA or messenger RNA. “This would very quickly give us an indication of the proteins that are being expressed by that patient, which gives us knowledge of the disease state at the point-of-care,” explained Ken Scarberry, a postdoctoral fellow in McDonald’s lab.

So far, the researchers have demonstrated a biosensing system with silicon nanowire sensors in a 16-well device built on a one-centimeter by one-centimeter chip. The nanowires, just 50 by 70 nanometers, differentiated between ovarian cancer cells and healthy ovarian epithelial cells at a variety of cell densities.

Silicon nanowire sensor technology can be used to simultaneously detect large numbers of different cells and biomaterials without labels. Beyond that versatile technology, the biosensing platform could accommodate a broad range of other sensors — including technologies that may not exist yet. Ultimately, hundreds of thousands of different sensors could be included on each chip, enough to rapidly detect markers for a broad range of diseases.

“Our platform idea is really sensor agnostic,” said Ravindran. “It could be used with a lot of different sensors that people are developing. It would give us an opportunity to bring together a lot of different kinds of sensors in a single chip.”

Genetic mutations can lead to a large number of different disease states that can affect a patient’s response to disease or medication, but current labeled sensing methods are limited in their ability to detect large numbers of different markers simultaneously.

Mapping single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), variations that account for approximately 90 percent of human genetic variation, could be used to determine a patient’s propensity for a disease, or their likelihood of benefitting from a particular intervention. The new biosensing technology could enable caregivers to produce and analyze SNP maps at the point-of-care.

Though many technical challenges remain, the ability to screen for thousands of disease markers in real-time has biomedical scientists like McDonald excited.

“With enough sensors in there, you could theoretically put all possible combinations on the array,” he said. “This has not been considered possible until now because making an array large enough to detect them all with current technology is probably not feasible. But with microelectronics technology, you can easily include all the possible combinations, and that changes things.”