Swine flu H1N1 virus more virulent than previously thought

23 July 2009

A new, highly detailed study of the H1N1 flu virus shows that the pathogen is more virulent than previously thought.

Writing in a fast-tracked report published in the journal Nature, an international team of researchers led by University of Wisconsin-Madison virologist Yoshihiro Kawaoka provides a detailed portrait of the pandemic virus and its pathogenic qualities.

In contrast with run-of-the-mill seasonal flu viruses, the H1N1 virus exhibits an ability to infect cells deep in the lungs, where it can cause pneumonia and, in severe cases, death. Seasonal viruses typically infect only cells in the upper respiratory system.

“There is a misunderstanding about this virus,” says Kawaoka, a professor of pathobiological sciences at the UW-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine and a leading authority on influenza. “People think this pathogen may be similar to seasonal influenza. This study shows that is not the case. There is clear evidence the virus is different than seasonal influenza.”

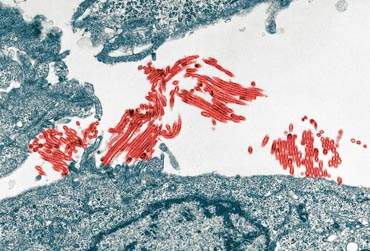

The pandemic H1N1 flu virus (red) has been shown to

be more virulent than scientists previously believed. The filamentous

shape of the virus, which in this image have recently budded from

infected cells, is also unusual.

Photo: courtesy Yoshihiro Kawaoka, University of Wisconsin–Madison

The ability to infect the lungs, notes Kawaoka, is a quality frighteningly similar to those of other pandemic viruses, notably the 1918 virus, which killed tens of millions of people at the tail end of World War I. There are likely other similarities to the 1918 virus, says Kawaoka, as the study also showed that people born before 1918 harbor antibodies that protect against the new H1N1 virus.

And it is possible, he adds, that the virus could become even more pathogenic as the current pandemic runs its course and the virus evolves to acquire new features. It is now flu season in the world’s southern hemisphere, and the virus is expected to return in force to the northern hemisphere during the fall and winter flu season.

To assess the pathogenic nature of the H1N1 virus, Kawaoka and his colleagues infected different groups of mice, ferrets and non-human primates — all widely accepted models for studies of influenza — with the pandemic virus and a seasonal flu virus. They found that the H1N1 virus replicates much more efficiently in the respiratory system than seasonal flu and causes severe lesions in the lungs similar to those caused by other more virulent types of pandemic flu.

“When we conducted the experiments in ferrets and monkeys, the seasonal virus did not replicate in the lungs,” Kawaoka explains. “The H1N1 virus replicates significantly better in the lungs.”

The new study was conducted with samples of the virus obtained from patients in California, Wisconsin, the Netherlands and Japan.

The Nature report also assessed the immune response of different groups to the new virus. The most intriguing finding, according to Kawaoka, is that those people exposed to the 1918 virus, all of whom are now in advanced old age, have antibodies that neutralize the H1N1 virus. “The people who have high antibody titers are the people born before 1918,” he notes.

Kawaoka says that while finding the H1N1 virus to be a more serious pathogen than previously reported is worrisome, the new study also indicates that existing and experimental antiviral drugs can form an effective first line of defense against the virus and slow its spread.

There are currently three approved antiviral compounds, according to Kawaoka, whose team tested the efficacy of two of those compounds and the two experimental antiviral drugs in mice. “The existing and experimental drugs work well in animal models, suggesting they will work in humans,” Kawaoka says.

Antiviral drugs are viewed as a first line of defense, as the development and production of mass quantities of vaccines take months at best.

Bookmark this page