Unexpected discovery of tuberculosis spores opens door for new treatment

17 June 2009

A close relative of the microorganism that causes tuberculosis in humans has been found to form spores. This is a sensational finding because researchers have long been convinced that these kinds of bacteria — mycobacteria — were incapable of forming spores.

Leif Kirsebom’s research group at Uppsala University now has photographic proof, obtained while working with the bacteria that causes tuberculosis in fish, to challenge this long-held belief. Their discovery, which has attracted much attention from other scientists, might constitute a new turn in the fight against human tuberculosis.

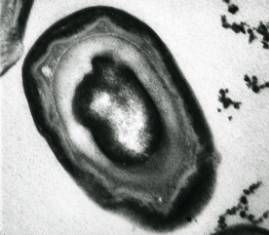

Photo of a fish tuberculosis spore

“This opens a completely new chapter in mycobacteriology. Now we can perhaps understand how mycobacteria ‘hibernate’ and cause latent infections,” says Leif Kirsebom.

To hibernate, many types of bacteria generate spores. Anthrax bacteria are a well-known example of this. Spores are stabile and can remain inactive for many years. Bacteria will often form spores when faced with harsh conditions, such as a drastic decrease in nutrition. However, the discovery that mycobacteria can produce spores means that even this group of microorganisms has the ability to hibernate.

The Uppsala research group’s pioneering discovery was completely unexpected. In fact, it was the result of a sidetrack in a study on something entirely different — RNA.

“In our studies we noticed something strange that we wondered about, but it wasn’t until I received funding to take up a completely new line of research that we took the opportunity to examine more closely the strange finding that we were seeing,” says Leif Kirsebom.

The microorganism that causes human tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, was identified in 1882 by the German microbiologist, Robert Koch. Every year ten million new cases of tuberculosis are diagnosed and two to three million people die of the disease.

Treatment is difficult because the microorganism is becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics. It is estimated that a third of the world’s population carries the microorganism latently, without any symptoms of the disease.

“This means that the disease can break out much later, even decades after the initial infection,” explains Leif Kirsebom.

Little is known about tuberculosis bacteria during this latent stage of the disease. It has been suggested that they are somehow “sleeping” or that their growth is retarded by the infected host’s immune system.

This lack of knowledge about how they hibernate applies to the other kinds of mycobacteria as well. Mycobacteria are found everywhere in our environment — in groundwater and tap water, in humans and animals.

Besides tuberculosis, they cause many other serious diseases, for example Buruli ulcer and leprosy in humans and Johne’s disease in cattle. Even the intestinal disease, Crohn’s, is believed to be linked to mycobacteria. The discovery that mycobacteria can form spores opens entirely new avenues to understanding how they hibernate and spread.

Bookmark this page