|

|

|

| Diagnostics | |

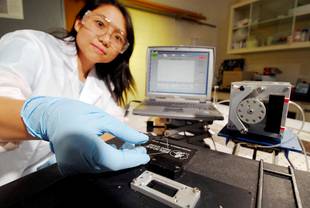

New sensor detects bird flu in minutes17 October 2007 A new biosensor developed at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) can detect bird flu (avian influenza) in just minutes. The biosensor is economical, field-deployable, sensitive to different viral strains and requires no labels or reagents. Quick identification of avian influenza infection in poultry is critical to controlling outbreaks, but current detection methods can require several days to produce results. “We can do real-time monitoring of avian influenza infections on the farm, in live-bird markets or in poultry processing facilities,” said Jie Xu, a research scientist in GTRI’s Electro-Optical Systems Laboratory (EOSL). Worldwide, there are many strains of avian influenza virus that cause varying degrees of clinical symptoms and illness. In the United States, outbreaks of the disease — primarily spread by migratory aquatic birds — have plagued the poultry industry for decades with millions of dollars in losses. The only way to stop the spread of the disease is to destroy all poultry that may have been exposed to the virus. A virulent strain of avian influenza (H5N1) has begun to threaten not only birds but humans, with more than 300 infections and 200 deaths reported to the World Health Organization since 2003. Looming is the threat of a pandemic, such as the 1918 Spanish flu that killed about 40 million people, health officials say. “With so many different virus subtypes, our biosensor’s ability to detect multiple strains of avian influenza at the same time is critical,” noted Xu. A study testing the sensor has been published in the journal Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. “The technology that Georgia Tech developed with our help has many advantages over commercially available tests — improved sensitivity, rapid testing and the ability to identify different strains of the influenza virus simultaneously,” said David Suarez, a collaborator on the project and research leader of exotic and emerging avian viral diseases in ARS’ Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory in Athens, Giorgia. Suarez is providing antibodies and test samples for GTRI’s research.

Sensitivity test The biosensor is coated with antibodies specifically designed to capture a protein located on the surface of the viral particle. For this study, the researchers evaluated the sensitivity of three unique antibodies to detect avian influenza virus. The sensor uses the interference of light waves, a concept called interferometry, to precisely determine how many virus particles attach to the sensor’s surface. More specifically, light from a laser diode is coupled into an optical waveguide through a grating and travels under one sensing channel and one reference channel. Current methods Current methods of identifying infected birds include virus isolation, real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RRT-PCR) and antigen capture immunoassays. Virus isolation is a sensitive technique, but typically requires five to seven days for testing. RRT-PCR is commonly available in veterinary diagnostic laboratories, but requires expensive equipment and appropriate laboratory facilities. RRT-PCR can take as little as three hours to get test results, but routine surveillance samples are more often processed in 24 hours. The antigen capture immunoassays can provide rapid test results, but suffer from low sensitivity and high cost. New sensor advantages Beyond the waveguide sensor, the only additional external components required for field-testing with GTRI’s biosensor include a sample-delivery device (peristaltic pump), a data collection laptop computer and a swab taken from a potentially infected bird. Power is supplied by a nine volt battery and USB connection. The waveguides can be cleaned and reused dozens of times, decreasing the per-test cost of the chip fabrication. Xu and Suarez are currently working together to test new unique antibodies with the biosensor and to test different strains. In addition, Xu is reducing the size of the prototype device to be about the size of a lunchbox and making the computer analysis software more user-friendly so that it can be field-tested in two years. “We are continuing our collaboration and have provided additional money to Georgia Tech to move the project along faster,” added Suarez. “Since this technology is already set up so that you can use multiple antibodies to detect different influenza subtypes, we are going to extend the work to include the H5 subtype.”

|