| Nanotechnology | |||

Solitons could power molecular electronics and artificial muscles18 July 2006 Solitary waves travelling through organic polymers could be harnessed to supply power in medical devices.

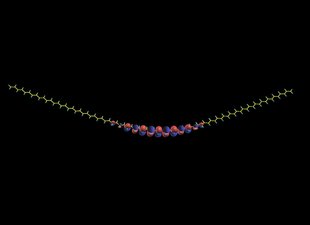

The polymer chains tend to bend and twist as solitons pass through them. This has led to the possibility of them being used to power artificial muscles for high-tech robots and devices to aid human mobility. Such muscles would be made of organic polymers, and flex in response to light or electrochemical stimulation. Solitons were first discovered in water in the 1840's by a Scottish Engineer, John Scott Russell, while observing a barge in a canal near Edinburgh (see Heriot Watt University's web page on Russell: www.ma.hw.ac.uk/~chris/scott_russell.html and Wikipedia for a description of solitons: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soliton). It was only in the 1960's when it was discovered that the theory of solitons could be applied to hydrodynamics, optics, plasmas, shock waves, tornados, elementary particles of matter and even the elementary particles of thought, that their importance was appreciated. Since the 1980s, scientists have known that solitons can carry an electrical charge when travelling through certain organic polymers. A new study now suggests that solitons have intricate internal structures. Scientists may one day use this information to put the particles to work in molecular electronics and artificial muscles, said Ju Li, Assistant Professor of materials science and engineering at Ohio State University. Li explained that each soliton in the organic polymers is made up of an electron surrounded by other particles called phonons. Just as a photon is a particle of light energy, a phonon is a particle of vibrational energy. The new study suggests that the electron inside a soliton can attain different energy states, just like the electron in a hydrogen atom. "While we know that such internal electronic structures exist in all atoms, this is the first time anyone has shown that such structures exist in a soliton," Li said. The soliton's quantum mechanical properties — including these newly discovered energy states — are important because they affect how the particle carries a charge through organic materials such as conducting polymers at the molecular level. "These extra electronic states will have an effect — we just don't know right now if it will be for better or worse," he said. Li and his longtime collaborators from MIT published their findings in a recent issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The name "soliton" is short for "solitary wave." Though scientists often treat particles such as electrons as waves, soliton waves are different. Ordinary electron waves spread out and diminish over time, and soliton waves don't. "It's like when you make a ripple in water — it quickly spreads and disappears," Li said. "But a soliton is a strange kind of object. Once it is made, it maintains its character for a long time." In fibre optics, normal light waves gradually flatten out; unless the signal is boosted periodically, it disappears. In contrast, solitonic light waves retain their structure and keep going without assistance. Some telecommunication companies have exploited that fact by using solitons to cheaply send signals over long distances. Before solitons can be fully exploited in a wider range of applications, scientists must learn more about their basic properties, Li said. He's especially interested in how solitons carry a charge through conducting polymers, which consist of long, skinny chains of molecules. The tiny chains are practically one-dimensional, and this calls some strange physics into play, Li said. In their PNAS paper, Li and MIT colleagues Xi Lin, Clemens Först, and Sidney Yip describe a detailed calculation of what happens to solitons at a quantum-mechanical level as they travel along a chain of the organic polymer polyacetylene. Their mathematical model builds upon a 1979 model called the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model. Alan Heeger, a University of California, Santa Barbara physicist who won the Nobel Prize in 2000 for his pioneering work on conducting polymers. Li said the new work extends the SSH model by including the full flexibility of the polymer chain, as well as interactions between electrons. The finding will likely affect the development of molecular electronics — devices built from individual molecules. "If fully understood, solitons may also be harnessed to drive molecular motors in nanotechnology," Li said. This work was mainly funded by Honda R&D Co., Ltd., with computing resources provided by the Ohio Supercomputer Center.

|