| Diagnostic imaging | |||

X-ray diffraction algorithm solves Sudoku puzzles29 March 2006 Cornell physicist Veit Elser and colleagues have discovered an algorithm critical for X-ray diffraction microscopy that gives researchers a new tool for imaging the tiniest and most delicate of biological specimens. They discovered that the same algorithm also solves the internationally popular numbers puzzle Sudoku — not just one puzzle, all of them.

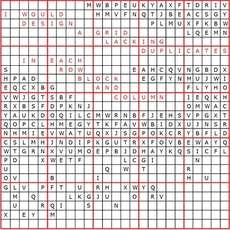

The Sudoku discovery appeals to Elser's whimsical side. But the algorithm, he notes, has potential for all kinds of other applications. "There are a lot of problems that you can represent in terms of this language," he says. The so-called difference-map algorithm, which Elser says could have applications from productivity optimization to nanofabrication, tackles problems for which the solution must meet two independent constraints. In the case of Sudoku, the constraints are simple: Each of nine numbers, considered alone, appears nine times in the grid so that there is only one per row and column. And all nine numbers appear within each of the nine blocks. In X-ray diffraction microscopy, the constraints are more complex. But the beauty of the algorithm, as Elser demonstrates, is that complexity doesn't matter. By applying the algorithm to the jumble of raw data from such an experiment, researchers can now reconstruct from it a clear, detailed image. The result, shown in images published with a recent article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) with lead author David Shapiro of the State University of New York at Stony Brook and other colleagues, is a richly detailed image of a specimen as small as a single yeast cell — taken without staining, sectioning or otherwise damaging the specimen. Unlike optical microscopes, which use a lens to focus light on a target (and are therefore only useful for specimens larger than the wavelength of visible light), imaging methods based on X-rays and electrons take advantage of the finer wavelengths provided by these forms of illumination. But some of these methods can damage the specimen with harmful radiation, require that a specimen be stained or otherwise altered or lack the penetrating power necessary for three-dimensional reconstructions. X-ray diffraction microscopy, which uses "soft" X-rays and measures the resulting diffraction pattern, is often the method of choice because it gives a detail-rich image and leaves the specimen relatively unscathed. The tricky part comes in using the diffraction pattern to reconstruct an image of the specimen. Instead of directly measuring the pixel-by-pixel contrast within the specimen, researchers are left with data that represents the object broken down into its constituent waves: a vast number of them, of different frequencies and amplitudes, waiting to be added up in a process called a Fourier synthesis to reconstruct the image. "But if it were just combining waves with a definite oscillation and adding them up, that would be a piece of cake for a computer to do," says Elser. The challenge is in the waves' phases, which are critical in reconstructing an image from the diffraction data. Without attention to that piece of the puzzle, the resulting image is reduced to noise. "People used to say that's an impossible problem," Elser says. "Then people got to thinking about the fact that there are going to be constraints coming from some rather mundane facts — that in principle will make the problem of deducing the phase like the solution of a solvable puzzle."

|